Issue: January 2024

Balance

Being a parent is hard work. We know that balancing everything life has to offer can be a challenge. As such we decided to do a series on Balance. Here you will be able to find tips to help you balance life a little better. We would love to hear how these tools and tips are working for you once you have implemented them (info@2motherhens.com).

Welcome to the fifth installment of the BALANCE series:

Children’s Nutrition and Diet

**Consistency is one of the most important aspects of effective parenting**

Parent’s Influence on Children’s Eating Habits

Parents powerfully shape children’s early experiences with food and eating, providing both genes and environments for children. Children’s eating patterns develop in the early social interactions surrounding feeding. As young omnivores, they are ready to learn to eat the foods of their culture’s adult diet and their ability to learn to accept a wide range of foods is remarkable, especially given the diversity of dietary patterns across cultural groups.

Parents select the foods of the family diet, serve as models of eating that children learn to emulate, and use feeding practices to encourage the development of culturally appropriate eating patterns and behaviors in children.

Children learn their eating habits early on from their parents. Research shows that babies are “taught tastes” even in utero. Foods their mothers eat tend to flavor amniotic fluid and breast milk.

Parents’ child-feeding practices are central in this early feeding environment and affect children’s food preferences and their regulation of energy intake. An understanding of how children’s food preferences are acquired is essential in developing strategies to improve the quality of children’s dietary intake.

Few food and flavor preferences are innate. Most are learned via experience with food. Their food preferences are shaped by their experience with those foods. Children decide their food likes and dislikes by eating and associating food flavors with the social contexts and the physiological (a general feeling or sensation that someone gets or has about something) consequences of eating.

The tendency for children to initially reject new or unusual foods is often just a case of neophobia (extreme or irrational fear or dislike of anything new or unfamiliar). Several studies have demonstrated that children’s preferences for and acceptance of new foods are enhanced with repeated exposure to those foods in a non-coercive setting. New foods may need to be offered to preschool-aged children ten to sixteen times before acceptance occurs. Therefore, children’s preferences and intake patterns are largely a reflection of the foods that become familiar to them.

At the same time, simply offering new foods will not necessarily produce liking. Having children taste new foods is a necessary part of the process. Awareness of this normal course of food acceptance is important because approximately 25% of parents with infants and toddlers prematurely drew conclusions about their child’s preference for foods after two or fewer exposures.

As stated previously, children learn about food through the direct experience of eating. However, they also learn by observing the eating behavior of others. Studies found that the selection and eating of vegetables by preschool-age children were influenced by the choices of adults and their peers.

Children’s intake of particular foods is influenced not only by the types of foods present in the home but also by the amount of those foods available to them. Recent studies provide evidence that show that large food portions promote greater energy intake by children as young as two years of age.

- When age-appropriate portions of an entrée were doubled in size, preschool-age children ate approximately 25% to 29% more than the age-appropriate portions of those foods, even though they consumed only two-thirds of the smaller portions of the entrée and were not aware of increases in the portion size.

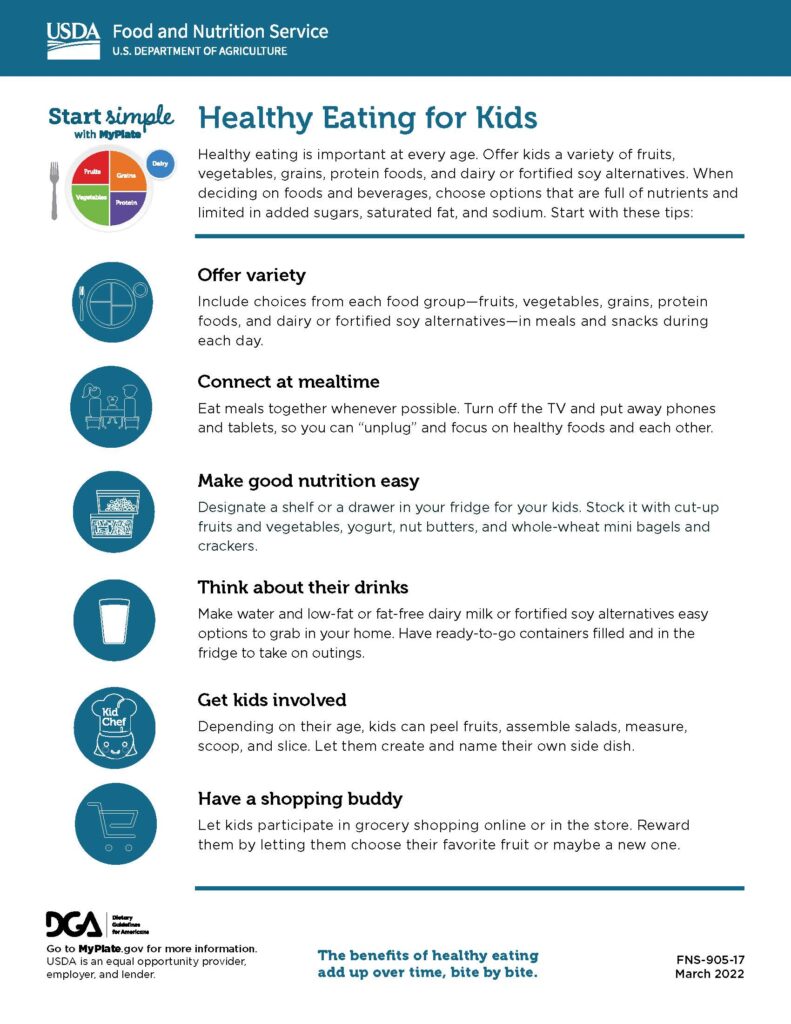

Tips to Follow:

- Rather than having lots of rules about food, have lots of conversations about food so that a meal isn’t just shoving food in but interacting in a fun way.

- One way to introduce balanced eating habits is to explore and discuss eating and food at the table. ‘Do you know where spaghetti comes from?’ Then look at videos about how to make pasta noodles or try making them.

- Cook together. We have found that if kids learn to cook healthy food early on, that is how they eat later. If “junk food” is only eaten occasionally in childhood, it usually remains an occasional addition to a healthy diet.

- If parents only have healthy snacks around and ready for snacking without preparation–like carrot sticks or apple slices in the fridge or tangerines to peel, then that’s what children grow up liking.

- If your cabinets and refrigerator contain only healthy food and if desserts like ice cream are a once-a-week occasion, and desserts or candy are not used as bribes, and if eating together as a family is a pleasant and regular experience, you’ve gone a long way to avoiding food issues later.

- It’s also important not to fall into “all or nothing” thoughts about eating. If you forbid yourself–or your kids–from having, for example, any food containing refined sugar or white flour, that may create even stronger desires for those ‘forbidden’ foods.

Parenting Style and Children’s Eating Behaviors

Traditional feeding practices used with infants and young children include feeding children frequently and quickly in response to distress, offering foods designed especially for infants and young children, offering preferred foods if possible, and encouraging children to eat as much as possible when food is available, often involving the use of coercion.

Parenting practices and parent-child interaction during feeding vary in the degree to which children are allowed some degree of autonomy in eating. These interactions can have a powerful influence on children’s developing food preferences, intake patterns, diet quality, growth, and weight status.

However, it is important to note that child-feeding practices may have unintended effects on children. For example, parents’ feeding practices often include attempts to increase children’s intake of nutrient-dense foods (e.g., “eat your vegetables”) or restrict children’s access to and intake of “unhealthy” or “junk” foods (e.g., “no, you can’t have any cookies now”). Parents using these practices may intend to promote healthier diets in children, and perhaps even prevent obesity, but the results of research reveals such attempts can have negative effects on children’s food preferences and their self-regulation of energy intake.

In general, parental control of feeding practices, especially restrictive feeding practices, tends to be associated with overeating and poorer self-regulation of energy intake in preschool-age children. The manner in which eating behavior is affected depends on the nature of the directive.

- For example, using food as reward for good behavior increased preschool-age children’s preferences for those foods, and because sweet, palatable foods are often used as rewards, this practice can have the unintended consequence of promoting children’s preferences for energy-dense palatable foods that are often unhealthy.

Parents may also reward children for consuming healthy foods in hopes of increasing children’s intake of foods such as vegetables. However, research has demonstrated that this practice can actually result in children learning to dislike and avoid those foods.

Restricting children’s access to “forbidden” foods also has a paradoxical effect on food preference and energy intake. Research reveals that placing a preferred food in sight, but out of reach, decreases children’s ability to exhibit self-control over obtaining the food. As a result, when restriction is lifted, and “forbidden” foods are present, children often have difficulty controlling the amount of food eaten, resulting in overeating and eating in the absence of hunger.

Excessive parental control and pressure to eat may also influence dietary intake and disrupt children’s short-term behavioral control of food intake.

- For example, studies have reported that higher levels of parental control and pressure to eat were associated with lower fruit and vegetable intakes and higher intake of dietary fat among young girls.

- Moreover, in a study of children’s feeding practices, encouraging children to eat by focusing their attention on the amount of food on the plate promotes greater consumption and makes children less sensitive to the caloric content of the foods consumed. Thus, pressuring children to eat their vegetables in order to leave the table or as a contingency to receiving dessert may ultimately lead to the dislike of those vegetables.

Controlling feeding practices are not likely used in isolation but rather represent the caregiver’s broader approach to child feeding.

- Authoritarian style of feeding in which eating demands placed on the child are relatively high, but responsiveness to the child’s needs or behavior is relatively low.

- Authoritarian feeding was negatively associated with vegetable intake.

- Authoritative style of feeding in which eating demands placed on the child are relatively high but tend to be highly responsive to the child’s eating cues and behaviors.

- Authoritative feeding was positively associated with the consumption of dairy, fruits, and vegetables and lower consumption of junk foods.

- Permissive styles of feeding which involve low demand and low responsiveness to the child are considered neglectful whereas those with low demand and high responsiveness to the child are indulgent.

Donations

Mother Hen is passionately committed to lending a helping hand to the underserved within the communities we serve. We are appreciative of any and all donations provided here. These donations will be used in entirety to provide services for underserved families as well as fulfill other specific outreach needs.

Outreach Initiatives:

- Community If your business would like to become a corporate sponsor and join us in supporting the community, please contact us directly.

- Family ServicesYour family service donation will directly help a family receive professional parental coaching sessions or services in navigating the school system to get the proper accommodations for their child to succeed academically.

- Corporate SponsorIf your business would like to become a corporate sponsor and join us in supporting the community, please contact us directly.